Tis almost fairy time!

by Fae Awareness staff member Sam Kelly

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (full text, Wikipedia) takes place almost entirely in the wild wood, which in Shakespeare’s day—before electric light industrialised logging, and the Ramblers’ Association—was still something to fear: a place of transformative change, a haunt of boar and brigand and quite possibly giant spider too. The tutelary genius of the forest is Puck, the provocative night-haunt, taunter of peasants, performer of everyday mischiefs. He’s utterly capricious rather than consistently malicious, though – his mischief, whether embarrassing or lethal, is born from the same source as the help he gives those who respect him. He may well be watching from behind any bush, perched in any tree, or talking to you in the likeness of a friend – and his master, Oberon, has motives both grand and utterly petty. His jealousy is understandable on a human scale (if repellent), but so is Titania’s maternal jealousy and her concern for the world. Because the fairies in Dream are very intimately linked to the land, their discord over Titania’s adopted changeling child causes the weather and the seasons to go completely screwy.

Titania: These are the forgeries of jealousy:

And never, since the middle summer’s spring,

Met we on hill, in dale, forest or mead,

By paved fountain or by rushy brook,

Or in the beached margent of the sea,

To dance our ringlets to the whistling wind,

But with thy brawls thou hast disturb’d our sport.

Therefore the winds, piping to us in vain,

As in revenge, have suck’d up from the sea

Contagious fogs; which falling in the land

Have every pelting river made so proud 460

That they have overborne their continents:

The ox hath therefore stretch’d his yoke in vain,

The ploughman lost his sweat, and the green corn

Hath rotted ere his youth attain’d a beard;

The fold stands empty in the drowned field,

And crows are fatted with the murrion flock;

The nine men’s morris is fill’d up with mud,

And the quaint mazes in the wanton green

For lack of tread are undistinguishable:

The human mortals want their winter here;

No night is now with hymn or carol blest:

Therefore the moon, the governess of floods,

Pale in her anger, washes all the air,

That rheumatic diseases do abound:

And thorough this distemperature we see

The seasons alter: hoary-headed frosts

Far in the fresh lap of the crimson rose,

And on old Hiems’ thin and icy crown

An odorous chaplet of sweet summer buds

Is, as in mockery, set: the spring, the summer,

The childing autumn, angry winter, change

Their wonted liveries, and the mazed world,

By their increase, now knows not which is which:

And this same progeny of evils comes

From our debate, from our dissension;

We are their parents and original.

Mortals – and particularly, their rituals and traditions – are an important part of this process, too. The fairy king’s jealousy of a mortal (adopted rather than stolen as in the “traditional” changeling myth) began it; the lack of hymns and carols angers the moon; and in the end, they cannot be reunited without the chance intervention of a brash bumbling mortal artisan. Since 1970, the play is often performed doubled: the same actors who portray the fairy court portray the court of Athens, with Theseus as Oberon and Hippolyta as Titania, showing the ambiguous way in which the fairy realm mirrors and echoes the mortal one. (Puck is also often doubled with Philostrate, the chamberlain & master of ceremonies in Athens.)

Speaking of ambiguity: Dream is even easier than most of Shakespeare’s plays to queer. Puck, particularly, is a focus for this, since his character’s protean enough that almost any kind of actor can play him: cis, trans, androgynous, very masculine, and very feminine actors have all done it well. Productions where there is no implied sexual (and/or kink) relationship between Oberon and Puck are increasingly in the minority, and a lot of directors choose to bring out sexual tension between Helena and Hermia as well. (To be fair, you have to work quite hard not to.)

Speaking of ambiguity: Dream is even easier than most of Shakespeare’s plays to queer. Puck, particularly, is a focus for this, since his character’s protean enough that almost any kind of actor can play him: cis, trans, androgynous, very masculine, and very feminine actors have all done it well. Productions where there is no implied sexual (and/or kink) relationship between Oberon and Puck are increasingly in the minority, and a lot of directors choose to bring out sexual tension between Helena and Hermia as well. (To be fair, you have to work quite hard not to.)

One other thing about fairies that modern productions of Dream makes really clear is that they are scary. Utterly, hypnotically, beautifully, terrifyingly scary. The kind of scary that could kiss you and make you never want to leave their bed, send a storm to destroy your crops in the field, lure your husband into a bog, and then abruptly leave you at the edge of the wood to make your own way home. And then, for good measure, balance a bucket of vitriol on the top of your bedroom door and send a really nice card at Christmas.

The scariness in recentish productions is not a new thing, but rather a return to older ideas of fairies; there’s been a big tendency to think of the Dream fairies as tiny, twinkly, sparkly things, like Tinkerbell without the jealous malice. This is partly down to Mendelssohn, whose saccharine, twinkling, swooping overture (composed in 1826 at the age of seventeen) set the artistic tone for almost every depiction of fairies in the English-speaking world for nearly a hundred years. Shakespeare’s original text was deeply unfashionable at that point—very crude and bawdy, and not nearly polished and artificial enough for the English stage. Nobody had performed Dream, except in rather bitty and sanitized adaptations, for decades; until Madame Vestris in 1840, nobody would. Mendelssohn’s Overture formed the core of his incidental music for the production, and has never fallen out of popularity since. (Vestris played Oberon, as it happens.)

After then, we had a succession of ever more complex sets and productions, culminating in Beerbohm Tree’s signature “stage full of crap” post-Victorian production of 1900, popular enough to be revived in 1905 and 1911 with live rabbits scampering about the stage. In 1914, Harley Granville Barker finally threw off the Victorian obsession with vast amounts of tat (preferably patterned and/or sparkly tat made in huge gloomy factories by small children) and presented an apron stage with futuristic columns and fairies painted gold.

Even without the gold paint, fairies present some staging problems – Shakespeare explicitly presents some of them as very small, enough so to dress in a snake’s shed skin or to make a coat from a bat’s wings, and of course you can’t do that with actors except by making the scenery much larger. Since Oberon & Titania are explicitly large enough to sleep with mortals, that’s not entirely a helpful approach on stage. Incidentally, the changeling boy (again, adopted, not stolen, as with the “standard” view of fae changelings) is sometimes played as a babe in arms, sometimes as a handsome young man – partly it depends on just how much the director wants to queer the performance. Children are often used to play the smaller fairies (including Puck, sometimes) but that doesn’t have to make them any less scary… we all know just how nasty and unpleasant children can be.

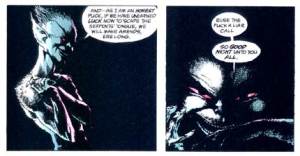

Like any good comedy, Dream ends with a wedding – in fact, three weddings and a reconciliation, alchemically restoring order to the discord-wrecked world. Weddings can’t just happen with a kiss, however, and after Will Kemp’s big dance number as Bottom the fairies return, blessing the house and its marriage-bed. Depending on your interpretation, Puck’s closing words are either innocently twee; a plea for the audience not to riot, they’ll get their money back; or utterly, utterly sinister. Neil Gaiman and Charles Vess’s interpretation, in Sandman: Dream Country, aims quite thoroughly for the last, but then as Peaseblossom says: “I am that merry wanderer of the night? I am that giggling dangerous totally bloody psychotic menace to life and limb, more like it.”

Like any good comedy, Dream ends with a wedding – in fact, three weddings and a reconciliation, alchemically restoring order to the discord-wrecked world. Weddings can’t just happen with a kiss, however, and after Will Kemp’s big dance number as Bottom the fairies return, blessing the house and its marriage-bed. Depending on your interpretation, Puck’s closing words are either innocently twee; a plea for the audience not to riot, they’ll get their money back; or utterly, utterly sinister. Neil Gaiman and Charles Vess’s interpretation, in Sandman: Dream Country, aims quite thoroughly for the last, but then as Peaseblossom says: “I am that merry wanderer of the night? I am that giggling dangerous totally bloody psychotic menace to life and limb, more like it.”

Jun 05, 2011 @ 17:49:28

Really enjoyed this piece, particularly: “One other thing about fairies that modern productions of Dream makes really clear is that they are scary. Utterly, hypnotically, beautifully, terrifyingly scary. “

Jun 06, 2011 @ 12:01:04

I definitely need to reread the play